Flying High

A Stanford-founded venture offers farmers a better snapshot of crop health.

Farmers face a Goldilocks dilemma every growing season. If they irrigate too much, they have to pay rising water costs and risk depleting their groundwater aquifer. If they irrigate too little, they risk diminishing crop yields. In order to maximize profit, they need to irrigate just right.

Optimizing irrigation and fertilizer is one of the primary challenges that commercial farmers face. The usual method for calibrating these variables is through their experience as well as plant and soil testing. For instance, to apply fertilizer a farmer sends plant leaves and soil for laboratory analysis of key nutrients such as phosphorous and nitrogen. After receiving the results several weeks later, the farmer then recalibrates the farm’s fertilization schedule.

The issue is that the sample takes a long time and may not be representative for the entire farm. What’s happening at the south corner of a field, near a creek, could be very different from what is happening in the middle, on a slight incline.

Farmers need a better perspective. A bird’s-eye view, you could say.

A new venture called Ceres Imaging, the brainchild of Ashwin Madgavkar, MBA ’13, is hoping to provide exactly that. Ceres is using aerial photography and spectral imaging to help farmers optimize water and nitrogen.

“We want this tool to completely replace tissue sampling,” he says. “That way farmers can make more informed decisions for their bottom line and the environment.”

Ceres uses a special camera system mounted on an airplane such as a crop duster, or sometimes a drone, to sweep over swaths of land collecting data. The airplane flies back and forth in neat rows like a push broom over the landscape, recording very thin slivers of light reflected from the crops below.

Like S-O-S signals flashing in the dark, it turns out the plants are speaking. “I’m thirsty.” “Too much nitrogen, that burns!” “I’m sick.” Certain patterns of light have certain meanings.

Ceres looks at six different spectral wavelengths of infrared and visible light and then correlates it with historical data from the ground. The team’s botanists and cellular biologists have spent countless hours doing groundwork with the University of California Cooperative Extension comparing the spectral light patterns emitted by crops with cellular tissue samples from the plants. This research helps them to interpret exactly what particular light “signatures” are saying.

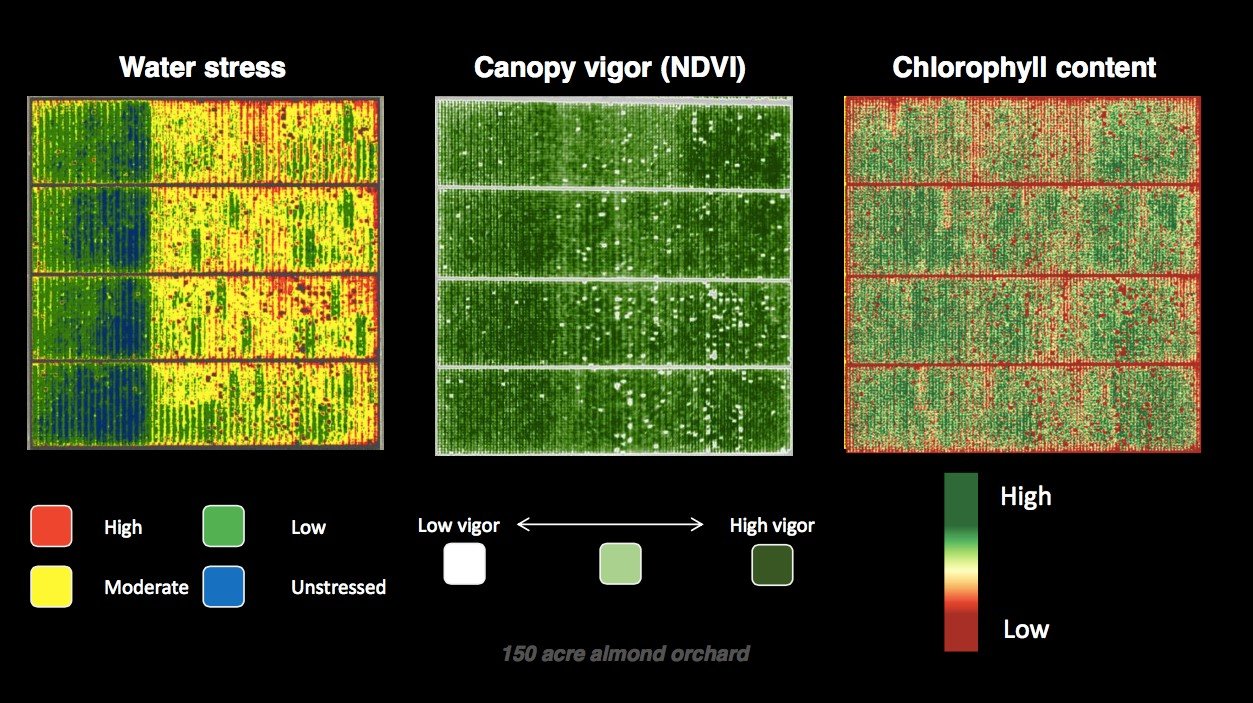

Farmers who subscribe to Ceres data services receive measurements of the water stress, canopy vigor, and chlorophyll content in their fields, along with an actionable plan based on the imagery. For example, when looking at water stress, Ceres has found that square or rectangular red zones indicate issues with the irrigation equipment, while blob patterns imply problems with the soil.

“Farmers are very pragmatic and at the end of the day if you can provide a product that will make more money than it costs them, then they will buy it,” says Madgavkar.

The payoff can be real. Red, highly stressed areas can decrease crop yields by 25 percent or more. Helping farmers detect problems in their fields sooner saves them money. Lowering expenses from water and nitrogen improves the farm’s margins, too.

Spectral imaging technology has been around for a long time. NASA started developing the technology several decades ago, but it hasn’t been effectively leveraged for agriculture in a commercial way until now.

Madgavkar conceived of the idea as a graduate student. He learned about “remote sensing” through his coursework in earth sciences and wondered about its marketability.

Curiosity kept him going. As a personal project, he spoke with 30 to 50 farmers from around the world asking them what metrics they wanted greater control over. He also spent time working at a large-scale sugarcane company in Brazil before enrolling in the Stanford MBA program.

Soon he found himself turning an esoteric academic field into a powerhouse commercial tool. Ceres Imaging now has 14 employees and operations in California and Australia, two places hard-hit by drought in recent years.

A grant from the TomKat Center for Sustainable Energy has allowed Ceres to explore whether their approach could work with holistic ranching, when ranchers move their livestock in herds meant to mimic the migration patterns of wild game and are able to improve the health of their pastureland. In the future, the venture may explore sustainable forestry too.

The Ceres approach has potential for true environmental gains. The technology can lead farmers to preserve groundwater supplies, decrease energy costs from pumping water, and reduce nitrogen pollution from over-fertilizing.

Perhaps most importantly, they are helping farms feed humanity with a smaller footprint, a challenge that will only grow as the world’s population approaches 9 billion.